“Improvement is a reality — Perfection, a liability.”

It took me some serious thinking to put to words the intent and moral message that I learned to embody in a very memorable year with one of my voice teachers. “Reframing” is the lingo that I’ve learned to assign to this lesson today, but back then I only knew it as the death of one way of thinking and the limping, awkward rebirth of another.

Lurking behind my quote above are three messages, the first of which is:

Searching for a momentary success is more valuable to a learner than spending an hour trying to attain perfection.

I learned this valuable lesson by listening to and making observations of the manner in which this teacher of mine conducted his singing lessons. Thankfully, I had a phone capable of recording, and a teacher encouraging the use of technology to facilitate learning. Lessons were goal-oriented, but not goal-driven. Accomplishment was weighed in “success of a moment” over “perfection in an hour.” When something wasn’t working after three subsequent tries, we moved on.

Yes, we moved on.

To the me of that time, it was unthinkable to let go of a task that I was unable to accomplish. The learner I had grown to be was fixated on “getting it” and not the journey that would eventually take me there. I’m sure other teachers tried to impart it to me through other means, but until that particular approach with that particular teacher at that particular point in my learning journey, it never clicked. Even in the thick of a lesson, I didn’t recognize that he was calmly and subtly nudging me along a path of “anti-fixation” while simultaneously measuring my achievement through small successes rather than large failures.

Being a student, what I took away were feelings.

I felt motivated. I felt happy after almost every lesson. I felt accomplished. I felt like I was getting somewhere.

It was addicting.

Because I didn’t spend the following week after a lesson depressed, moody, and fixated on all the things that weren’t perfect, I went back to each lesson more invigorated and excited to learn and grow than ever before. So happy was I with these lessons, in fact, that I started questioning how was this happening. How could my learning experience have changed so drastically from years before?

It was only with reflection and deep observation that I was able to finally “pin the tail on the donkey,” so to speak. I started listening back to my lessons not with the ears of a student, but with the ears of a teacher. I had experience teaching by that point, as I had done it for a few years, but never before had I listened to lessons to figure out “how is he getting me to do that” because I was so used to listening back and thinking “how am I doing that.”

Which brings me to the second message hiding behind my quote:

It’s not the result that matters but how you get there.

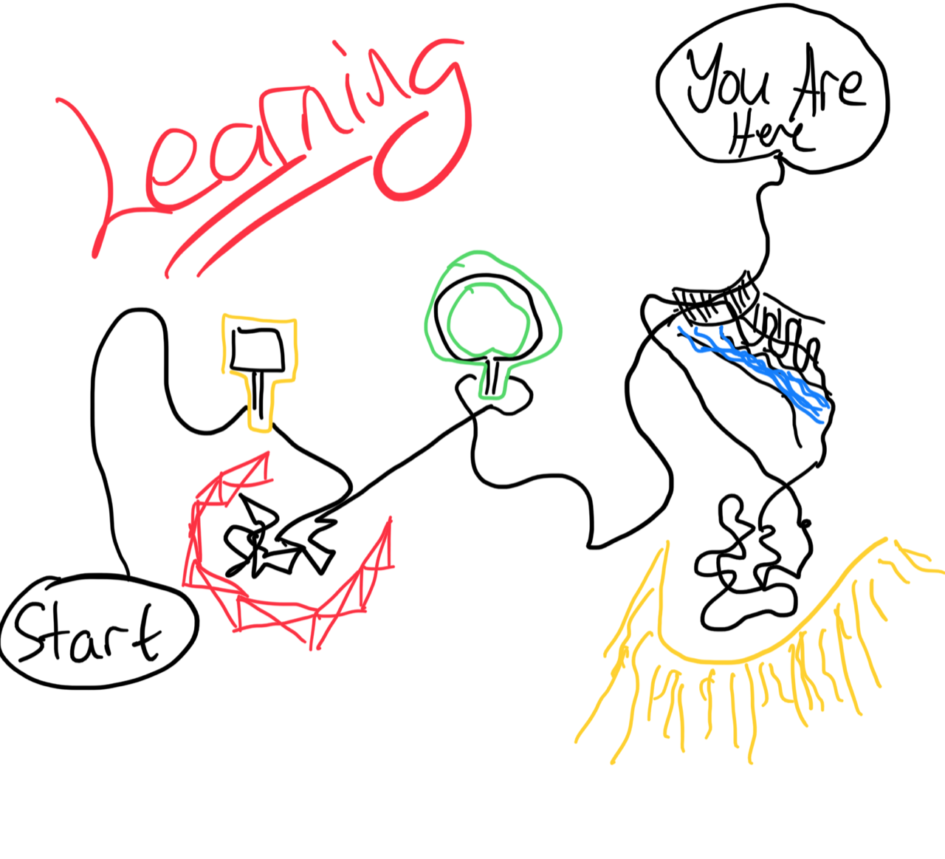

A winding path of temporarily abandoned tasks filled with millions of small successes is the best way to learn. This is THE most important lesson I have learned to apply to my pedagogy. Not only does it keep momentum going and moods uplifted, but you get farther in the long run anyway. I accomplished more of my long term singing goals in that one year than I did in the three years previous, and all it took was reframing my thought process to follow a new framework.

There was a new lingo, a new perspective, and a new manner of measurement…

Which brings us to:

There is no failure. There is success, and less success.

That’s right. Failure in learning is a figment of our imaginations. That’s not to say that the definition of failure does not exist. If there was a pressure vessel that failed its safety inspection but got used and sold to a customer anyway and then later EXPLODED while sitting next to a bunch of other pressure vessels and caused a massive SECONDARY EXPLOSION that cost lives and millions of dollars worth of damage, we would call that a failure. Just saying. But if we examined a situation in which lives weren’t at risk, such as testing the safety features of a vehicle with a crash dummy, we can reframe “failure” into “less than successful.” For example, overall the test could be successful, with less successful elements within that frame. And those less successful elements would then inform the direction that the team would approach to improve the safety features of the vehicle.

The same concept can be applied to teaching.

Let’s take math as an example. We put three problems in front of the student. They do not get the right answer for all three. Instead of fixating on the “mistakes,” we focus on the “successes.” We frame our feedback in a positive manner, such as:

“Your addition and subtraction are spot on. Great job with that. What tripped you up a bit was just remembering to subtract from both sides when doing algebra. If we want to isolate for y, then this 4 needs to go away. You totally got that. Our next step is remembering to always do to one side as you do to the other. Think of it this way: we treat others the way we want to be treated. You’re the y, and “everybody else” is on the other side of the equals sign.”

The addition and subtraction were successful, and following the “rules of algebra” was less successful. If we can teach our students to reframe their way of thinking into “that was successful” and “that was less successful,” then the underlying psychological impact of language on the learning process can switch people’s minds from being infected and obsessed with the virus that is perfection to being overjoyed with a winding journey of small successes and achievements. Almost like a video game or something, hm…?

The lessons I took away from my experience:

1. Searching for a momentary success is more valuable to a learner than spending an hour trying to attain perfection.

2. It’s not the result that matters but how you get there.

3. There is no failure. There is only The Force — JUST KIDDING — There is success, and less success.

“Improvement is a reality — Perfection, a liability.” — Morgan Traynor

Leave a Reply